Leela is an ancient game of self-knowledge, the history of which goes back more than two millennia. Neither the author nor the time of the invention of this game are known. However, in ancient times, in many cultures of the world, the name of the creator was not considered important and significant, because he only fulfilled the will of God, was his hand and the instrument of creation.

The playing field represents the player’s life path, illustrated by virtues (steps) and flaws (snakes). Knowing their inner states and freeing themselves from the bondage of passions, players move from lower levels of consciousness to higher ones in order to achieve freedom in merging with the Higher Mind.

Many versions of Leela and its origins have been recorded. In world museums there are about 50 variants of boards for the game, most of which are found in different regions of India, Nepal, Tibet. Unfortunately, descriptions of inner states (as they were in antiquity) have not survived.

The game Leela is presented in many religious traditions and philosophical schools: there are Jain, Hindu, Sufi versions of it, etc. There is also evidence of Buddhist versions of the game during the Pala Sena period.

Gyan Chauper (“The Game of Wisdom”), Jnana bazi / Gyan bazi (“The Game of Heaven and Hell”), Leela (“Spending Time”), Vaikunthapaali, Thayam, Parama Pada Sopanam (“Steps to the Highest”), Kismet, Moksha Patam (Steps of Salvation), SHATRANJ-AL-ARIFIN (Chess of the Wise), Nagapasa, Snakes & Ladders are all names of one game.

There were many variations of the playing field: 72, 84, 101, 124, 132, 342 squares and other non-standard versions. The most common game boards were 8 × 8, 10 × 10 or 12 × 12 squares. The location of the snakes and steps also varies. Each player is represented on the playing field by a certain symbol. Traditionally, a cube with 6 sides was used to move around the playing field.

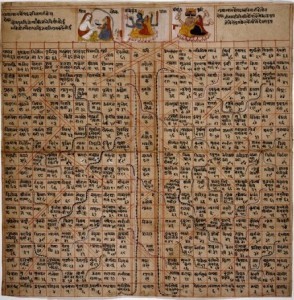

JAINIST PLAYING FIELD

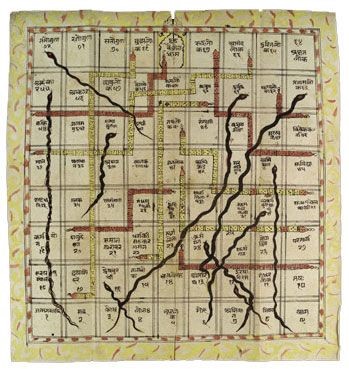

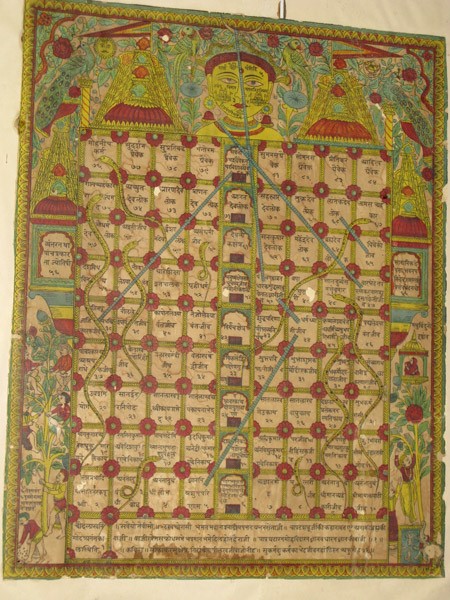

The oldest surviving version of the game is Jain. It is dated 1735 and found in Rajasthan.

The playing field of this version was most often made of dyed fabric, the so-called “patas”.

The traditional Jain field consists of 84 squares: 9 × 9 squares with three additional squares (1, 56 and 66).

Another name for the game is Jnana Bagi (Gyanbazi or Gyanbaji), which has been known since the 18th century as the “Game of Heaven and Hell”.

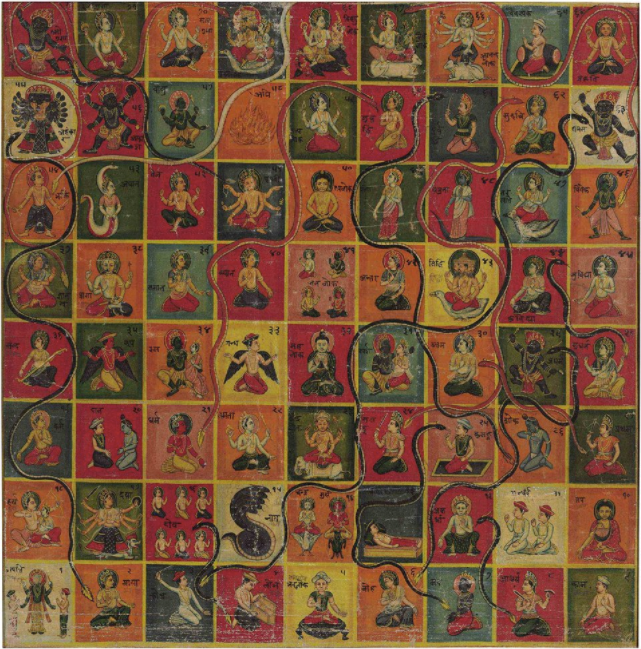

Gyan Chaupar (Jain version of the game), National Museum in New Delhi

Jnana bazi, XIX century, gouache on fabric

Jainism

Jainism preaches respect for all living beings. The philosophy and practice of Jainism consists primarily in the self-improvement of the soul to achieve omniscience, omnipotence and eternal bliss. Any soul that has overcome the body shell remaining from previous lives and attained nirvana is called Gina. A person can communicate directly with God (the Absolute), earn salvation by their deeds and thoughts without the mediation of a brahmana priest and without numerous sacrifices.

Despite the fact that the religious and moral teachings of India are closely intertwined, Jainism is a separate teaching with its own philosophy.

There are at least eight characteristics that distinguish Jainism from the Vedic religion and Hinduism. They are so essential that they do not allow Jainism to be considered a religion of Hinduism or any other component. In ancient times, the difference between the representatives of Hinduism and Jainism was so noticeable that it gave rise to classifying them as different races.

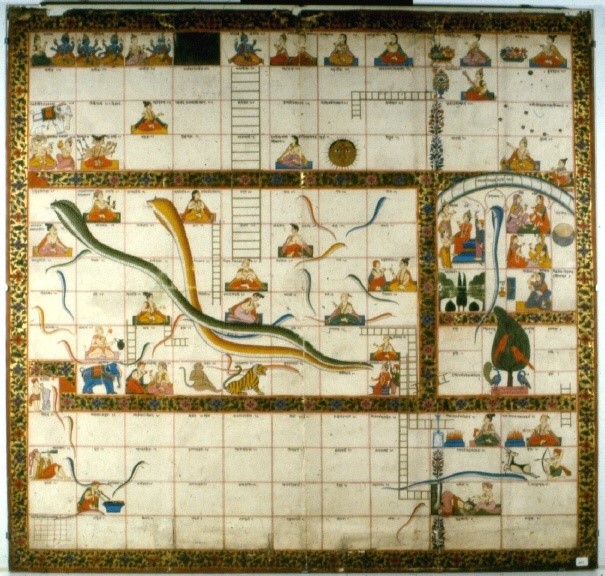

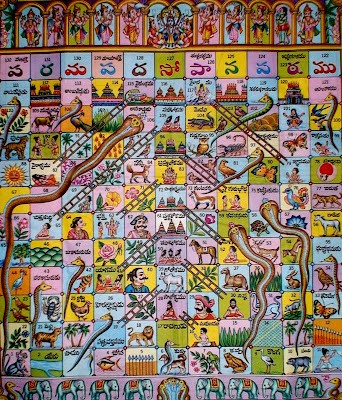

HINDU VERSION OF THE GAME

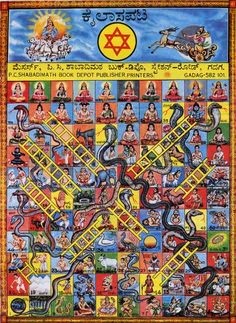

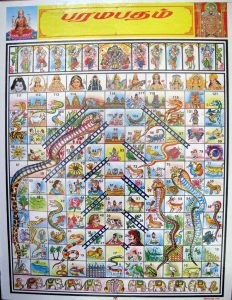

The Hindu version of the game was the most popular among the Brahmins. The traditional Hindu playing field was significantly different from the Jain one (both in format and in terminology). Over time, many variations of Hindu game boards have emerged. There are versions with 100 or more squares.

Basically, the game preached Vaishnavism (a direction of Hinduism, a distinctive feature of which is the worship of Vishnu and his avatars). There are game boards from the beginning of the 19th century, on which Vishnu is depicted as Krishna.

The Hindu version of the ancient game was first described by Harish Johari in 1980 in his book Leela. The Game of Self-Knowledge, which is published in many countries of the world. In the Russian-speaking space, it was offered by the Sofia publishing house. The book can be found now on the Internet.

Gene Chaupar. Field of 72 squares

Hinduism

The term “Hinduism” refers to a collection of diverse traditions that hold the authority of the Vedas, which are considered one of the oldest scriptures in the world. Most Hindus recognize the Divine reality that creates, maintains and destroys the Universe, and believe in the Universal God, who is simultaneously inside every living being and manifests itself in a variety of forms.

Typical beliefs in Hinduism:

- dharma – moral duty, ethical obligations;

- samsara – the cycle of birth and death, belief in the reincarnation of the soul after death into animals, people, gods;

- karma – the belief that the order of rebirth is determined by actions performed during life and their consequences;

- moksha – liberation from the cycle of birth and death, samsara;

- yoga (its various directions).

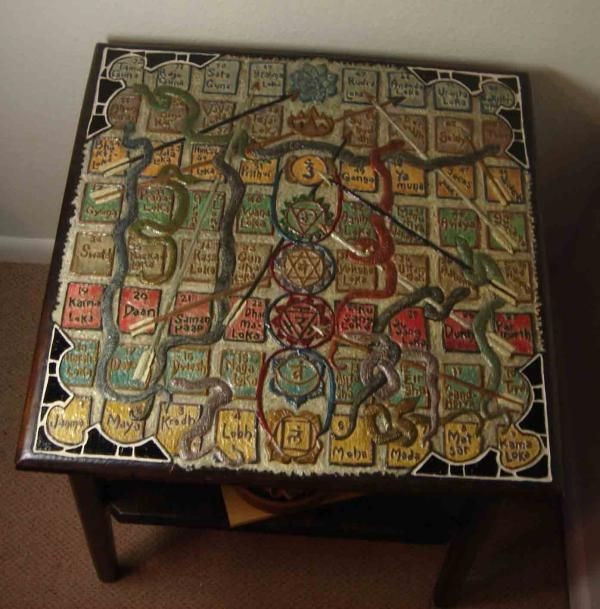

Modern Hindu playing field acquired at Ranganathaswamy Temple in Shirangam (India)

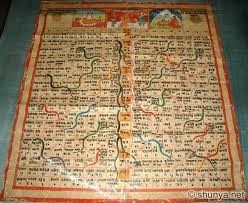

MUSLIM (SUFI) VERSION OF THE GAME

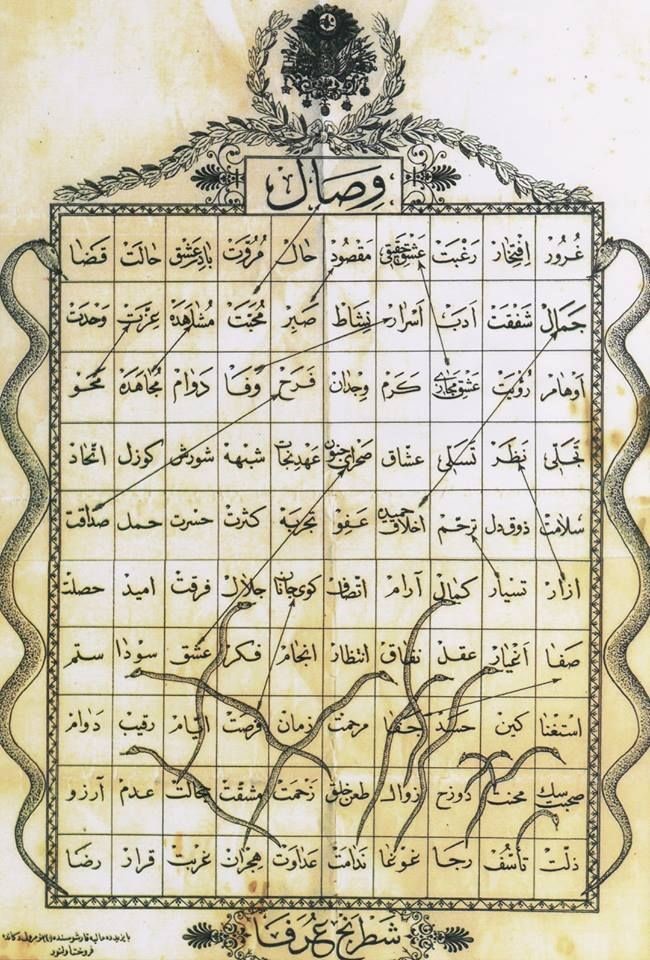

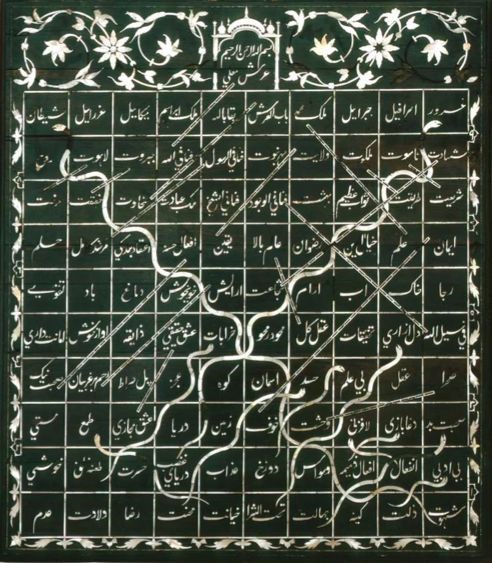

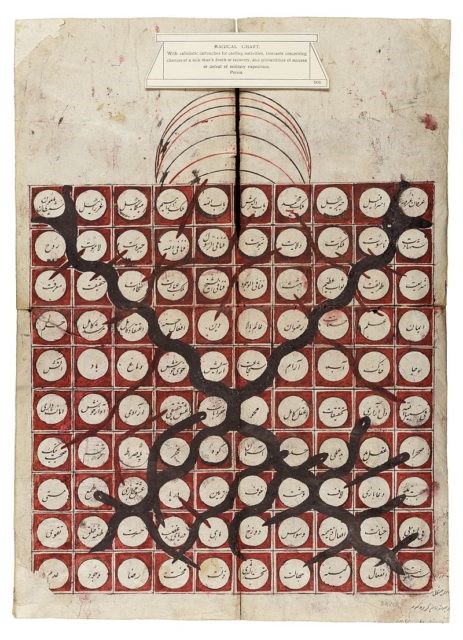

The Muslim version of the game was used in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Its playing field traditionally consists of 100 squares, symbolizing the number of names of God, and 101 squares – the Abode of Allah. The writing on the field is Arabic (Persian). There are 17 steps and 13 snakes on it. Subsequently, this slightly modified version became known as SHATRANJ-AL-ARIFIN, or “Chess of the Wise”.

Sufism

Sufism is an ancient tradition of spiritual development, one of the main directions of classical Muslim philosophy. The goal of Sufism is to comprehend absolute reality, to educate a “perfect person” capable of perceiving the truth, free from worldly vanity and able to cope with their negative qualities.

Sufi Shatranj al-Arifin. Persian serpents and steps, 19th century, Ajmir (India)

OTHER GAME VERSIONS

There are also copies of the game for 124 cells, in which the field of 14 x 10 is divided into separate zones; a large playing field with 342 squares and other non-standard versions.

NAGAPASA

In Nepal, versions of a 72-square playing field (9 × 8 format) have been discovered. This game was called Nagapasa.

Two types of writing were used on the playing field: Persian (Arabic) and Devanagari (Old Indian).

The game includes both Hindu and Muslim flaws and virtues.

BUDDHIST NAGAPASA

Each square contains a Buddhist figure. There are blue, red and white snakes on the field. The steps were replaced with red / good snakes and the white snake led to liberation.

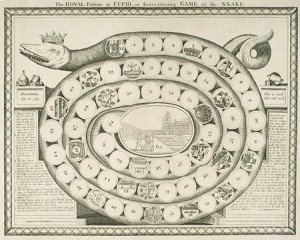

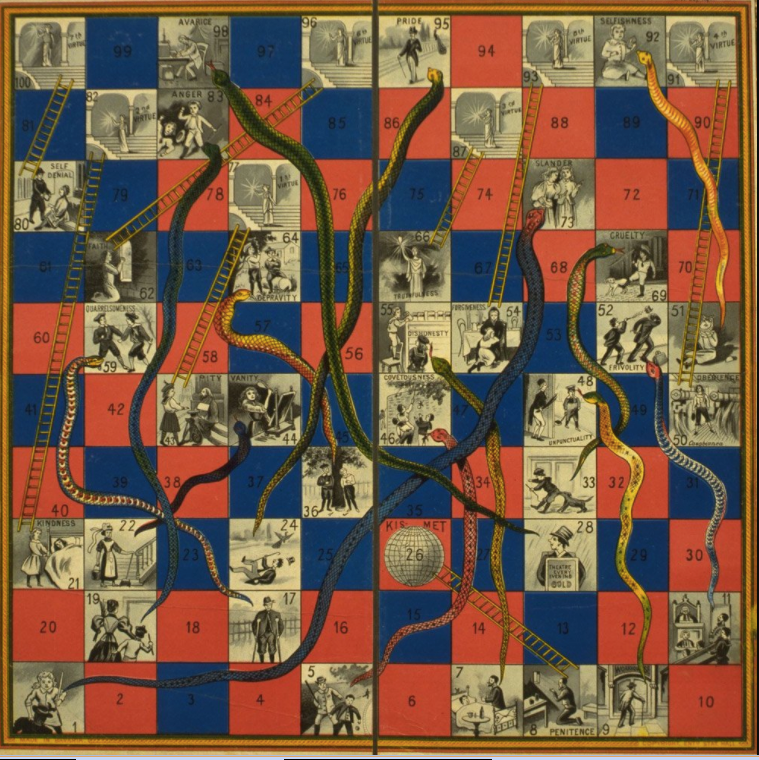

SNAKES & LADDERS / CHAIRS AND LADDERS

In 1982 this game was brought to England and adapted for local players. Indian virtues and flaws were replaced by English ones, reflecting Victorian morality. Originally known as Kismet, the game became popular as Snakes and Ladders.

The lesson of the game was that a person grows above himself, doing good, and doing evil, degrades and descends to a lower level of life. The number of snakes and ladders in the Victorian version of the game was the same to illustrate that each person has at least one chance to correct an indecent act with a good deed, and at any time at least one temptation may occur on the player’s path, which will inevitably lead to a fall.

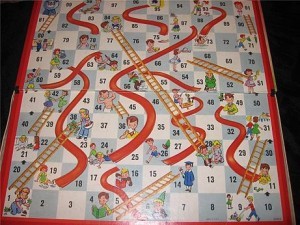

CHUTES AND LADDERS

In 1943, Milton Bradley released the game Chutes and Ladders in the USA. Its simplicity has made it one of the world’s best-known classic board games.

The playing field is 10 x 10, symbols are moved using a spinner (instead of a cube). The snake appears as a ribbon. The point of the game is to teach toddlers to understand the causes and consequences. The squares at the bottom of the ladder illustrate children doing good or clever deeds; at the top of the ladder are children enjoying a reward; the squares at the top of the ribbon depict children who are mischievous or have distinguished themselves by inappropriate behavior; at the bottom of the ribbon, children are depicted suffering from the consequences of such behavior. Another point of the game is to teach resistance to the ups and downs that inevitably happen in life.

London. Ring metro line. Mosaic based on the game “Snakes and Ladders”.

“Snakes and Ladders” at Kilmarnock Primary School, Scotland